Christian worship and gatherings evolved significantly, transitioning from intimate gatherings in private residences to the grand construction of public basilicas. This transformation marked a pivotal shift, as private, hidden worship transformed into a visible, public act that resonated deeply within the community. As congregations grew not only in size but also in significance, these impressive structures became essential gathering places, serving as focal points for the faithful and reflecting the multifaceted nature of their beliefs. They encapsulated not just the faith of individuals but also the collective aspirations and cultural identity of society as a whole. This new repurposing of Roman architecture played a crucial role in accelerating a new reality for communities, advancing God’s Story of Grace. They fostered an environment that brought together a new sacred space of joining personal dignity, which was reinforced by communal identity—concepts that would prove foundational to Western social thought. This laid the groundwork for future social and cultural developments that would evolve throughout the centuries.

In this article, we will examine how the basilica as a new place of gathering advanced God’s Story of Grace, forming the image of the trinity in society, which built a new understanding and experience that was both personal (the many) and communal (the one).

From Private Persecution to Public Legitimacy

In the Roman Empire’s first three centuries, the emerging Christian community gathered for worship in private homes, a necessity due to periods of persecution and the need for discreet assembly. This was a testament to their unwavering belief and resilience as followers of Jesus. These informal, intimate spaces fostered a sense of close fellowship, centered around shared meals (the agape feast), instruction, and discipleship. Early Christian meetings were humble affairs. Believers assembled in the homes of wealthier members like Lydia or Prisca and Aquila, as noted in Paul’s letter (1 Corinthians 16:9). The architecture was entirely domestic, with rooms adapted for prayer, baptisms (often in a modified courtyard or a separate room), and communal worship. The house at Dura-Europos in Syria is a famous archaeological example, showing a simple residential structure modified into a meeting place.1 This “house church” model was a necessity during a time when Christians were often a marginalized group and could not build public places of worship.

The narrative shifts dramatically in 313 AD, when Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which granted Christianity legal status and full tolerance within the Roman Empire. This act not only ended official persecution but also thrust the Church into public prominence. Christianity moved from the shadows of persecution into the light of imperial favor. The faith exploded in popularity, attracting masses of new converts, and the modest house churches could no longer accommodate the growing congregations. The newly public Church needed a new architectural form. Christian leaders, with imperial patronage, chose to adapt the Roman basilica, which was a public multi-purpose building used for law courts, markets, and public assemblies. This was chosen over the pagan temples for several reasons:

- Capacity: The large, rectangular, open interior could house an entire congregation for communal worship, which pagan temples (designed for only a few priests inside who offered sacrifices) could not. The vast, open interior of the basilica, designed to hold large crowds, was perfect for accommodating growing congregations.

- Association: Unlike pagan temples, which were deeply rooted in the traditional Roman religious practices, the basilica had no strong ties to these customs, allowing the Church to effectively distance itself from polytheism and create a new identity that resonated with its distinct Christ-centered beliefs and practices.

- Dignity: As an official Roman public building, the basilica form already commanded respect and authority, bringing a greater degree of respect to a once marginalized faith. By establishing basilicas as public buildings, Christians moved from the shadows of persecution into the light, becoming central landmarks in cities that reinforced Christianity’s growing prominence and role in civic life.

They did not just adopt the building; they baptized it. They saw the potential of the basilica’s vast, open interior, perfect for large numbers of the faithful to gather and hear the Word.

From Cultural Resistance to Public Influence

The story of the church moving from homes and even underground dwellings (catacombs) to basilicas is one of Christianity transforming the culture by its missional movement. This transition marked a pivotal moment in history, signifying not just a physical change in location but also a profound shift in how Christianity engaged with the broader world. This physical adoption had profound and immediate consequences for Western civilization and God’s work in the world:

The Architecture of Community

By adopting the basilica, the church established a communal space as the core of its physical expression, ensuring that worship could be accessible to all members of the community. Unlike the mystery cults or pagan rituals that often took place in private or exclusive temples, Christian worship in the basilica was public and inclusive, inviting individuals from all walks of life to participate in the sacred rites. The architectural choice of the basilica not only provided a grand and welcoming environment but also symbolized the openness and universality of the Christian faith. This design encouraged greater interaction among congregants, fostering a sense of belonging and connection within the community.

The Enduring Framework of Western Law

The shift from the magistrate’s judgment seat to the bishop’s teaching chair was a seismic transfer of authority. The basilica was the physical embodiment of Roman law. When the Western Roman Empire crumbled and the legions retreated, the only organized authority that remained was the Church. The legal and administrative framework that had once been dispensed from the secular apse (arch) was now administered from the spiritual one. The Church adopted Roman legal principles, canon law, and administrative organization, all housed within the familiar basilica structure. This ensured the survival of Roman legal thought as the empire crumbled under the foot of barbarian invasion. The very concept of a structured, institutional body of law—a cornerstone of Western governance—endured because its physical home was preserved and repurposed by the Church.

The Birth of the Public Square

The Christian basilica created a new kind of gathering place: a structured space for moral instruction, reflection, and community gathering. This became the model for countless public institutions throughout Western history, from town halls to university lecture halls. It established the idea of a dedicated, formal civic space that was not just for commerce or military assembly, but for the higher purpose of social and moral cohesion. Today, when you walk into a modern courthouse, a state capitol building, or a university hall with its central aisle and raised platform, you are walking through the architectural ghost of the Roman basilica.

What Happened to House Churches?

House churches continued into the fourth and fifth centuries, even as larger, dedicated church buildings became more common after Christianity was legalized. While formal structures like basilicas emerged, many Christians continued to meet in homes. The shift from house churches to dedicated buildings was a gradual one. In many cases, existing private homes were remodeled for Christian worship, sometimes incorporating features like baptismal baths. Even with new, large churches being built, it was not always practical or desirable for all Christians to gather in one place. Smaller, more intimate house church settings remained important for many communities. In some regions, Christians continued to meet in homes due to ongoing persecution or simply because it was more accessible or preferred than using a large, public building.

Conclusion

The decision made by early Christian leaders—to utilize the remnants of the empire for the construction of their places of worship—accomplished more than merely providing a sanctuary for the church. It preserved the principles of structured law, defined the essence of communal gathering spaces, and significantly influenced the physical and philosophical landscape of the West. This development represented a progression in God’s Story of Grace by integrating a new space to cultivate the Trinitarian image within society, emphasizing personal dignity alongside communal identity.

____________________________________________________________________

- The Dura-Europos house church was a private home in the ancient city of Dura-Europos (modern-day Syria) that was converted into a Christian meeting place around 240 AD. It is significant as one of the earliest known Christian assembly buildings, featuring well-preserved frescoes, particularly in the baptistery, that depict biblical scenes like the Good Shepherd and the Healing of the Paralytic. The conversion involved architectural changes, such as removing walls to create a larger meeting hall and adding a baptistery with a font, which made it suitable for Christian worship while remaining discreet.

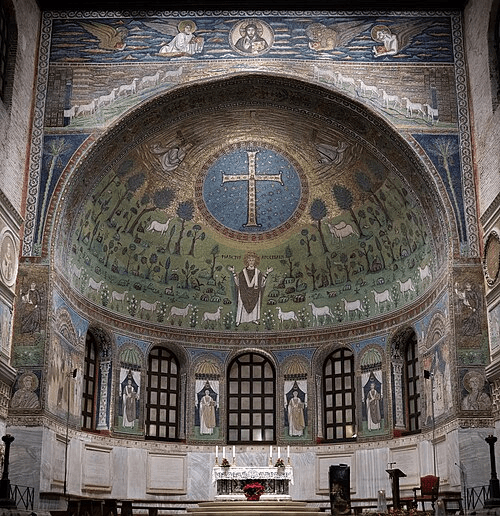

- The basilica—from the Greek basilike, meaning “royal”—was a symbol of that power. It was the civic heart of every Roman town: a spacious, rectangular hall with a raised apse at one end, where a magistrate sat in judgment, administering justice and collecting taxes. It also featured high central ceilings with clerestory windows for light.

- Ancient mystery cults often conducted their core rituals in private, exclusive temples or designated sacred spaces, distinct from the public, state-sponsored religious ceremonies. The very term “mystery” (from the Greek myein, to shut one’s eyes or lips) refers to the secrecy surrounding their rites. Only individuals who had undergone a special initiation process (mystai) were permitted to participate, and they took vows of secrecy, often under penalty of death for revealing the details. Mithraea: The cult of Mithras, popular among Roman soldiers, conducted its rituals in small, windowless, often underground temples called mithraea. These were the architectural “antithesis” of open public temples. Sanctuaries and Shrines: Major cults like the Eleusinian Mysteries had dedicated sanctuaries where secret ceremonies took place in a central, restricted hall (the Telesterion). Private Settings: Beyond formal temples, some rites, like those of Bacchic groups, were held in private voluntary organizations (thiasoi), sometimes in remote locations like mountains, to engage in ecstatic worship away from public view.

Previous article: The Latin Vulgate: How Jerome’s Bible Defined a Millennium of European Culture