Christianity brought the first nonviolent revolution that changed the world from the inside out through conversion and discipleship. Far from causing violence, in its first 300 years, it was the brunt of periods of localized to widespread and systematic persecution and outright cruelty. This was experienced from the beginning (see Acts 8:1-4). The majority of its adherents were mostly poor, with little to no social status or influence. The Roman Empire consisted of 60 million people living over 2 million square miles (the continental United States is just over 3 million square miles), with over 30 nations and dozens of cultures connected by 250,000 miles of roads. The social and cultural barriers were vast, and the conditions were often hostile and dangerous. Yet, in 300 years, it went from a few hundred adherents to 35 million people (57% of the Roman Empire). Below are the projected conversion growth rates according to Rodney Stark1:

- 7,500 Christians by the end of the first century (0.02% of sixty million people);

- 40,000 Christians by 150 AD (0.07%)

- 200,000 by 200 AD (0.35%)

- 2 million by 250 AD (2%)

- 6 million by 300 AD (10%)

- 34 million by 350 AD (57%)

Nothing like this type of revolution had ever occurred anywhere in the world. To imagine that in its early days (anywhere before AD 250), it would become the dominant religion in the whole Empire would be beyond the wildest imagination. The question before us is how did the liberating power of the Holy Spirit spread from Pentecost to reach and transform millions in just three centuries? The heart and core of the answer lies in the command Jesus gave to his first followers just after the resurrection:

“Therefore go and make disciples of all nations…”

Matthew 28:19

In this article, we will trace the early expansion of Christianity and then examine the core reasons that caused it to grow so dramatically. In this, we will see that Christianity emerged as the first decentralized mass movement of people, bringing new levels of personal freedom to millions while being linked to the same life and truth of the gospel. God further shaped humanity into the trinitarian image with increased liberty (diversity) and one gospel (unity).

Initial Messianic Movement

The Jesus’ movement started within Judaism. At Pentecost (AD 33), there were 3,000 who believed in Jesus as the Messiah. (Acts 2:41) Many of these were visiting Jerusalem from sixteen different locations outside the sacred city, some as far as Rome, 2,500 miles away. (Acts 2:9-10) Among the thousands who embraced Jesus as the Messiah, they would have taken their newfound faith back to the places where they resided and started embryonic churches.2 There was a Christian group in Damascus (about 140 miles north of Jerusalem) maybe as early as AD 34.3

It is largely believed that a church was started in Rome by those who returned to that capital city from Pentecost. Many budding churches started as Jews returned to their places of residence after Pentecost. Nearly twenty-five years later (ca. AD 57), James and the elders at the Jerusalem church affirmed that many thousands of Jews believed:

You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law. (Acts 21:20)

When it is stated that many thousands believed, the Greek term used is μυριάς (muriad), meaning ten thousand. Had there been ten thousand by this date, that would mean, overall, that Jesus’ movement made very little impression upon the Jewish people. Emperor Claudius took a census of the Roman Empire (AD 48), and it revealed that there were 7 million Jews in the Roman Empire, with 2.3 million in Israel.4 Perhaps around 400,000 were in Alexandria, Egypt. If these numbers are accurate, that would mean that 1/10th of 1% of the Jewish population embraced Jesus as the Messiah. That would hardly be a ripple in the ocean of the Jewish world at the time.

Paul and the Gentile Movement

With the conversion of Cornelius (Acts 10), the first Gentile believer, to Jesus’ movement around AD 40, a pivotal shift began to occur. The Christian faith would become predominantly Gentile in a short period of time, maybe as early as the mid-first century. The apostle Paul, though not alone, was central to accelerating this shift. By AD 49, when Paul reached Thessalonica, his opponents proclaimed:

“These men who have caused trouble all over the world have now come here…” (Acts 17:6)

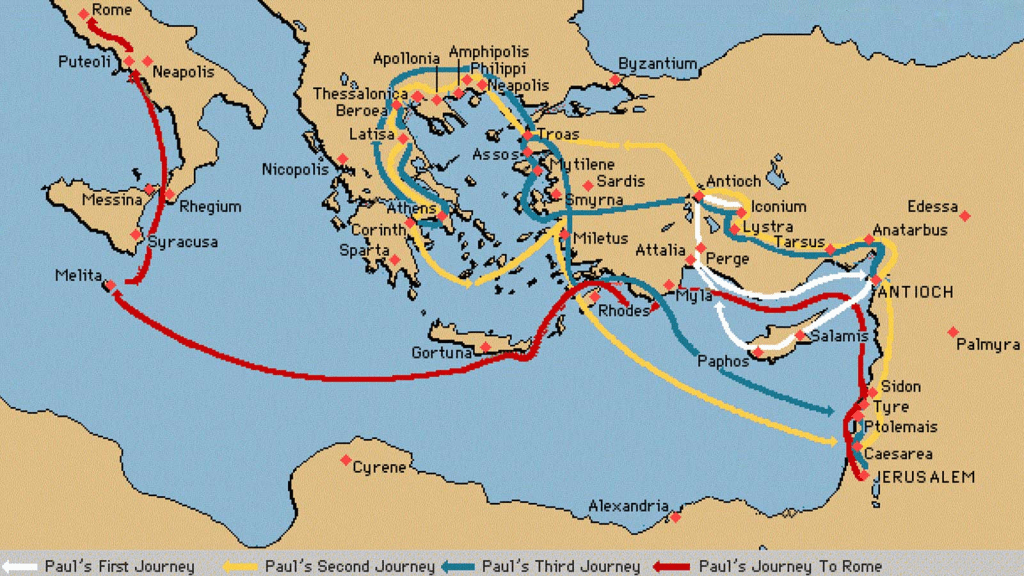

Paul was formidable in taking Christianity in a westward direction (as the map above shows Israel, Syria, Turkey, and Greece) on his three missionary journeys which occurred over 13 years. (Acts 13-14, 16-17, 18:23–20:38) Though Paul was a notable missionary of Jesus’ movement, the spread of the faith took place through thousands of disciples, the vast majority unmentioned in the records of history.

300 Years Into 3 Continents

By AD 100, the Church had been largely established in all parts of the Roman Empire. Rodney Stark points out that of the 17 cities which were 1,000 miles from Jerusalem, 12 had a congregation by AD 100. All of the 17 cities had one congregation by AD 180. Of the 14 cities more than 1,000 miles from Jerusalem, 8 cities had one congregation by AD 180. By AD 250, all of them had a church.

Asia

Antioch: This became the second major home and hub of the Christian movement outside of Jerusalem. It was the third largest city in the Roman Empire, boasting 500,000 residents by the end of the third century. It is here that the gentile identity of Jesus’ movement was formed, as they were the first to be called Christians. (Acts 11:26) The church was predominantly Greek-speaking and spread throughout much of Syria. By the time of the Council of Nicaea (AD 325), the church had no less than 20 bishops from Syria present.5 This indicates the presence of the faith in many towns and cities in several different parts of the region.

Ephesus: We know little of the missionaries who labored here after Paul. One exception is the account of Gregory Thaumaturgos, known as the “Worker of Wonders.” This man, a son of prominent and wealthy parents, was a native of Pontus. In the course of his studies, he became a Christian. In the year AD 240, he was made bishop. He set out to preach the gospel to the pagans of his region. It is said that when he ascended to leadership, only seventeen Christians were there, while thirty years later, at his death, only seventeen pagans remained.

Edessa: The church spread to Edessa (southeastern Turkey). At this point, in the first century, it lay just beyond the Roman Empire, yet it had close ties with Antioch. It was later claimed that the founder of the church there had been one of the 72 disciples of Jesus (Luke 10:1-3), a man named Addai. According to Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History, a terrible illness had stumped the court physicians of King Abgar, ruler of Edessa. In his desperation, he prayed to Jesus, pleading with him to come to his capital of Edessa. Eusebius records that the apostle Thomas commissioned Thaddeus to go there. “When he came to these places, he both healed Abgar by the word of Christ and astonished all there with the extraordinary miracles he performed.” Serapion, bishop of Antioch in about AD 200, consecrated an Edessene Christian named Palut to be bishop of the capital. From here, the gospel would spread to regions that are now Iraq, Armenia, and India.

Armenia: According to tradition, the disciple Thaddeus (Matthew 10:3) arrived in Armenia in AD 43, where he was joined by Bartholomew (Mark 10:3) in AD 60. Both men are said to have died there as martyrs. We also know that Syriac missionaries from Edessa reached Armenia by the third century. The traditional account, however, honors Gregory the Illuminator (AD 257–331) as one who advanced Christianity in Armenia. Gregory was himself an Armenian, a prince who was educated as a Christian in Caesarea (present-day Turkey). Upon his return, he found himself, like Daniel in Babylon, imprisoned in a pit by the monarch Tiridates III (reigned AD 287–330) for refusing to participate in pagan sacrifices. Gregory was recalled from his pit after twelve years to cure Tiridates, who had descended into a mysterious state of madness.

India: There is a body of evidence that shows the apostle Thomas traveled east, through Syria and Iraq, and reached India. He is believed to have landed on the Malabar Coast (present-day Kerala) and established one of the world’s oldest Christian communities.6

Europe

Rome: Peter preached in Judea and Samaria, before traveling to Antioch, Asia Minor (Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, and Bithynia), and finally to Rome.7 Christianity appears to have had a significant presence in the city of Rome by the late AD 40s. This rapid growth can be partly attributed to the large number of Christians who converged on Rome from other parts of the Empire. Paul referenced all of the disciples who had moved there from different parts of the world as evidence of this in Romans 16.8 There were some 30,000 Christians there by AD 250. Most were poorer and spoke Greek, which was the language of the lower classes, as opposed to Latin.

France: Christians from Rome went as missionaries to France, known at that time as Gaul. Irenaeus (AD 130-200), a prominent bishop in France, speaks of using both the Celtic and Latin languages, which would indicate that the church had gone beyond the Romanized people in France.9 By the end of the third century, many churches had been established in Spain.

Africa

Egypt: North Africa became rich with churches. Mark (Acts 12:12, 25; 15:37), who was the writer of the biblical gospel that bears his name and a traveling companion of Peter, was reported to have founded the Church of Alexandria around AD 49. There are further indications that he established the gospel presence in Libya, which was his place of birth. Simon of Cyrene (Matthew 27:32, Mark 15:21, and Luke 23:26), who carried the cross of Jesus, was also believed to be a strong influence in Libya. Alexandria was an especially strong center, producing such Christian thinkers as Clement (AD 150-c215) and Origen (AD 185-254).

Ethiopia: Christianity became the official religion of Ethiopia during the reign of King Ezana (AD 320-360). Irenaeus of Lyons (see above), writing in AD 180, reports that Simon Backos preached “the coming in the flesh of God” in his homeland of Ethiopia. Going back even further, Luke writes of the 1st-century conversion of an Ethiopian official (Acts 8:26-40). Could this official have started the first church in Ethiopia? In that it became the official religion of the nation in the fourth century, it is reasonable to think that it underwent at least a few centuries of steady Christian development.

Tunis & Algeria: There was rapid growth further west in what is today known as Tunis and Algeria. The churches here were the first Latin speaking churches. And out of them flowed some of the great Latin Christian literature of Tertullian and Cyprian, to be followed later by the famous Augustine. Augustine resided in modern day Algeria.10

What Caused Christianity to Grow?

Root Cause # 1: A contagious move of the Spirit. The fire of the Holy Spirit, starting at Pentecost, would ignite a transforming and unstoppable blaze from person to person to person. As God’s Story of Grace spread, millions of people discovered a new identity and empowerment to live lives of purpose beyond anything their culture provided for them. This is what Jesus promised would happen through the power of the Holy Spirit:

But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth. (Acts 1:8)

Root Cause # 2: The message of the gospel. The message of the gospel was seen as the only and ultimate Good News for all of humanity to bring righteousness before God:

16 For I am not ashamed of the gospel, because it is the power of God that brings salvation to everyone who believes: first to the Jew, then to the Gentile. 17 For in the gospel the righteousness of God is revealed—a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: “The righteous will live by faith.” (Romans 1:16-17)

It was this message that led to a rapid spread:

6 You became imitators of us and of the Lord, for you welcomed the message in the midst of severe suffering with the joy given by the Holy Spirit. 7 And so you became a model to all the believers in Macedonia and Achaia. 8 The Lord’s message rang out from you not only in Macedonia and Achaia—your faith in God has become known everywhere. (1 Thessalonians 1:6-8)

Root Cause # 3: An exponential reproduction of discipleship among everyday believers. The movement of the Christian faith was a decentralized movement of everyday people who were equipped and trained to disciple more everyday people. As Paul writes:

Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. (1 Corinthians 1:26)

One evidence of this is that in the first three hundred years, the church faced several waves of violence and cruelty. In some cases it was very severe and was meant to severely cripple and wipe out the faith. Yet, these persecutions never worked because the early church was faithfully engaged in training and maturing leaders and missionaries to continue the spread of the gospel. As Paul instructed Timothy:

And the things you have heard me say in the presence of many witnesses entrust to reliable people who will also be qualified to teach others. (2 Timothy 2:2)

For example, when severe persecution hit the Jerusalem church, they had to locally disband. Luke records that the persecution had a reverse effect:

1On that day a great persecution broke out against the church in Jerusalem, and all except the apostles were scattered throughout Judea and Samaria. 2 Godly men buried Stephen and mourned deeply for him. 3 But Saul began to destroy the church. Going from house to house, he dragged off both men and women and put them in prison.4 Those who had been scattered preached the word wherever they went. (Acts 8:1-4)

What is significant is that it was not the apostles who spread out. They stayed in Jerusalem. When Paul was jailed in Rome, he described the emboldening effect it was having on other believers:

12 Now I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that what has happened to me has actually served to advance the gospel. 13 As a result, it has become clear throughout the whole palace guard and to everyone else that I am in chains for Christ. 14 And because of my chains, most of the brothers and sisters have become confident in the Lord and dare all the more to proclaim the gospel without fear. (Philippians 1:12-14)

Because Christianity was so decentralized it led to an exponential spread of the faith. Like interest in an investment, it grew slowly at first but then rapidly gained exponential momentum. At the root of all of this is that the church, in the power of the Spirit, discipled everyday believers, in the gospel of Jesus.

Conclusion

Christianity unleashed a decentralized movement which snowballed from thousands to millions of converts in 300 years. It brought a new movement of compassion and care, equality and dignity, freedom and purpose to everyday people. It expanded the realization of personal freedom in unparalleled ways. The world advanced in the shape of the Trinity coming to greater personal freedom. To make this sustainable, it would need to find a unity within all of the new diversity which was created on three continents and in dozens of countries and cultures. This diversity could lead to schisms and break in the church. God would have a solution to this. So the Story of Grace continues…

_____________________________________________________________

- Stark would be the first to admit that those figures are anything but precise, but they provide plausible limits.

- Small groups of people with with a loose affiliation who were following Jesus through simple practices of discipleship which were modelled for them. (see Acts 2:42-47)

- Because Paul went to arrest and detain Christians there, this is evidence of a church formed very early on. Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples. He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any there who belonged to the Way, whether men or women, he might take them as prisoners to Jerusalem. (Acts 9:1-2)

- This number is not agreed upon by scholar. Yet, it is safe to sat that this number is in no way unreasonable.

- Church organization consisted of a bishop (higher ranking leader) overseeing several churches in an area.

- Sean McDowell writes: Early church writings consistently link Thomas to India and Parthia. Three points stand out regarding their witness to Thomas. First, the testimony that he went to India is unanimous, consistent, and reasonably early. Second, we have no contradictory evidence stating Thomas did not go to India or Parthia or that he went elsewhere. Third, fathers both in the East and in the West confirm the tradition. Since the beginning of the third century it has become an almost undisputable tradition that Thomas ministered in India. In addition to the traditions about Thomas in India, there is additional evidence that Christianity made it to India by at least the second century, if not earlier.

- While the Bible doesn’t explicitly state his presence in Rome, many early Church Fathers, like Irenaeus and Clement of Rome, wrote about Peter’s ministry and leadership in the Roman church.

- France was divided into Romanized and non-Romanized areas.

- Marg Mowczko writes, “Of the twenty-nine people, ten are women, and seven of the ten women are described in terms of their ministry (Phoebe, Prisca, Mary, Junia, Tryphena, Tryphosa, Persis, and perhaps Rufus’s mother also). By comparison, only three men are described in terms of their ministry (Aquila, Andronicus, Urbanus), and two of these men are ministering alongside a female partner (Aquila with Prisca, Andronicus with Junia). These are numbers worth remembering.”

- The theologian Thomas Oden has pointed out that the Christianity in Africa influenced the Christians in Europe well before European Christian would influence Africa.