In this third and final article on the influence of Aristotle, we will see that the great philosopher significantly contributed to God’s Story of Grace by introducing what is called virtue ethics. Virtue ethics emphasizes the development of moral character (virtues) through repeated behaviors to cultivate a life which advances human flourishing. Aristotle was not really concerned with laying down strict rules for moral choices or considering the best outcomes of actions; rather he wanted ethics to focus on how an individual’s character leads to virtue creating a life of blessedness (similar to the beatitudes of Jesus in Matthew 5:3-10). We will consider, then, the unique contribution of Aristotle’s thought on ethics and how it shaped the world’s understanding and experience of moral development. We will tie this into how virtue ethics enriches our understanding of Christian discipleship.

What Is the Ultimate Purpose of Ethics?

Eudaimonia the Goal

The ultimate aim of ethics can be summed up in the word: eudaimonia. This is a Greek term first used by Aristotle in the context of philosophy. The word carries the idea of “flourishing.” Sometimes the word is translated “happiness” or “well-being.” When translated “happiness” it does not refer to a temporary state of good feelings; it rather describes a life that is lived well that brings a growing experience of moral satisfaction–fulfillment. This is the “good life,” and in the ethical sense there is no other end or higher purpose beyond it. Thus, this eudaimonia, in Aristotle’s thinking, is the proper aim or goal of all human action. He describes this as follows in his work, Nicomachen Ethics:

Now happiness, more than anything else, seems complete without qualification. For we always choose it because of itself, never because of something else. Honor, pleasure, understanding, and every virtue we certainly choose because of themselves, since we would choose each of them even if it had no further result; but we also choose them for the sake of happiness, supposing that through them we shall be happy. Happiness, by contrast, no one ever chooses for their sake, or for the sake of anything else at all.

Virtue the Means

But how does one gain this human flourishing? Aristotle makes the case that this is by the cultivation and exercise of virtue. Again from Nichomachean Ethics: “…the human good proves to be activity of the soul in accord with virtue…” What is meant by this activity of the soul is that virtue is attained by the ongoing practice of virtuous acts. He further explains, “We become just by doing just actions, temperate by doing temperate actions, brave by doing brave actions.” After the virtues have become a habit (a normal behavior) through practice, they bring a transformation of character. This character can be defined as to who we really are and how we are really inclined to act. It has been more popularly expressed as who we are when no one is looking. For Aristotle virtue is not a rote habit but something deeper in the soul. It is a trained habit of soul which guides our moral compass where our choices will shape the outcome of our life. A modern expression of Aristotelian thinking goes as follows:

Thoughts Become Words, Words Become Actions, Actions Become Habits, Habits Become Character, Character Becomes Your Destiny.

The Golden Means

A central concept in Aristotle’s thinking is the golden means. Virtue is not only right action flowing from habits that develop into character; it also entails a wisdom of deciding the right action from situation to situation. This means that virtue, as Aristotle explains, “is a mean between two vices [golden means], one of excess and one of deficiency.” Author and teacher, Brett Kunkle, provides the following elaboration and helpful chart:

The mean balances virtue between two extremes. For instance, when we examine the virtue of courage we come to see that it is balanced between the appropriate feelings of fear and confidence. Too much confidence leads to rash action, yet too much fear leads to cowardice. The individual who has attained the virtue of courage avoids both vices when he experiences the appropriate amount of fear or confidence in a particular situation.

| Activity | Vice—Deficiency | Virtue—Mean | Vice—Excess |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facing loss or death | Cowardice | Courage | Rashness |

| Bodily appetites or pleasures | Insensibility | Temperance | Intemperance |

| Giving money | Stinginess | Generosity | Extravagance |

| Retribution for wrong | Injustice | Justice | Revenge |

By using the golden means Aristotle is not prescribing general rules, but rather a guiding principle. The guide is grounded in a wisdom which has developed the ability to choose the right action in specific cases.

Humanities teacher, Brett Saunders, provides this illustration:

Suppose I am shopping with my daughter and she is affronted by some fellow. The “right” intervention, according to Aristotle, falls between cowardice and recklessness, perhaps as a mix of cautious de-escalation and definitive show of strength. What the mean looks like for a specific act depends on the circumstances—why, how, with whom, and how much the agent acts, as well as who the agent is. Considering these variables and hitting the mean with regard to, for instance, the time of day, absence of other shoppers, appearance and manner of my daughter’s accoster, proximity or absence of security personnel— this belongs to the virtue of prudence. As a sort of keystone virtue, prudence stands out from others (self-control, justice, friendship, etc) because it is the capacity for considering the variables and determining the “mean” act (not too late or soon, not too bold and timid, not too abrasive or deferential) in the proper amount of time. Prudence is the knack of taking the right amount of time to decide on the right action.

The Lasting Legacy of Aristotle’s Ethics

A lasting influence on education.

Aristotle grounded ethics in the ideas of human flourishing and virtue. This was quite substantial for the influence of Western Civilization which emphasized the formation of character development in education. If virtue is not emphasized at the youngest age, then it is impossible to have a virtuous society. To bring about virtue in youth, Aristotle emphasized (what is another Greek term) paideia. This word means “child” but it became the shorthand for the training and education of children which cultivates virtue. Paidea had four emphases:

- Stories. There was a focus on the action of heroes to deeply impress the imaginations of the young. Literature was a key facet of paideia because it forms the heart with its deepest desires, values, and loyalties.

- Music. This was an influence carried over to Aristotle from Aristotle’s teacher, Plato. Plato focused attention on music “because rhythm and harmony most of all insinuate themselves in to the inmost part of the soul and most vigorously lay hold of it in bringing grace with them.”

- Gymnastics. Gymnastics largely meant physical training to the Greeks. The physical training refined the whole person: intellect, imagination, sensibilities and the body.

- Imitation. The Greek term used for this is mimesis (where we get our word mimic). Aristotle saw this as the soul’s imitation of the pattern from another human being. More simply put is was about having proper role models.

A lasting influence on ethics.

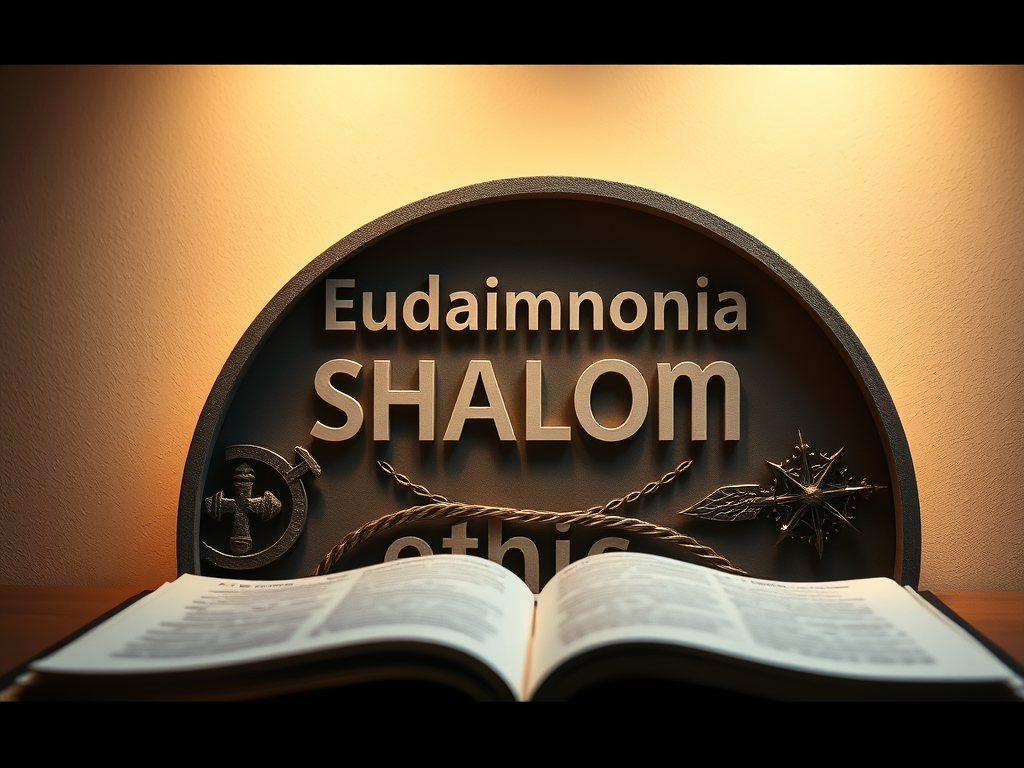

After Aristotle, society could begin to think in richer ways about the goals of being a community or to live together as a human family. From Persia, the world saw the spread of the empire, which did allow for the protection of certain religious and cultural freedoms. From the earlier Greeks (e.g. Cleisthenes), the world saw the introduction of democracy and ways for it to be practiced. But the deeper question for Aristotle was what are these different forms of government for? He would answer eudaimonia or human flourishing. The idea is not to have any ideal form of government (democracy, empire, etc.), but to understand that the role of government is to promote human flourishing or moral happiness. In the Old Testament a somewhat equivalent term for eudaimonia is shalom. Shalom in Hebrew means “wholeness” or “well-being.” These are both concepts that describe a life of flourishing or a life lived as it is meant to be. Theologian Cornelius Plantinga beautifully captures the meaning of shalom:

The webbing together of God, humans, and all creation in justice, fulfillment, and delight is what the Hebrew prophets call shalom. We call it peace, but it means far more than mere peace of mind or a cease-fire between enemies. In the Bible, shalom means universal flourishing, wholeness, and delight…. Shalom, in other words, is the way things ought to be.

So, in Aristotelian and biblical thinking the political form of government we adopt is a mean toward an ends: eudaimonia or shalom. The Declaration of Independence reflects this thinking in the phrase “the pursuit of happiness.” The goal of politics is to develop societies where virtue is taught and practiced and the interest of the whole can be balanced with personal freedom for increased flourishing. (This is the trinitarian model which sees flourishing as a balance of the one and the many.)

A lasting influence on Christianity

The biblical call to discipleship is centered around developing the character of our lives to become like Christ. Paul expresses it very simply: “…train yourself to be godly.” (1 Timothy 4:7) Though Christianity did not derive its understanding of discipleship from the Greeks, the ways of Jesus reflect some of what Aristotle taught. For after all, Aristotle did not invent the pursuit of virtue but discovered its reality. Repeatedly the Bible refers to how our circumstances are training us to walk in Christ-like maturity (virtue):

2 Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of many kinds, 3 because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance. 4 Let perseverance finish its work so that you may be mature and complete, not lacking anything. (James 1:2-4)

Again…

28 And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose. 29 For those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son… (Romans 8:28-29)

Summary

There are many more scriptures which could be listed. But let’s close with a statement from C.S. Lewis, in his essay “The Weight of Glory” as he explains that biblical ethics is not simply about obeying raw commands, but they are geared toward the formation of positive blessing or eudaimonia:

If you asked twenty good men today what they thought the highest of the virtues, nineteen of them would reply, Unselfishness. But if you had asked almost any of the great Christians of old, he would have replied, Love. You see what has happened? A negative term has been substituted for a positive…. The negative idea of Unselfishness carries with it the suggestion not primarily of securing good things for others, but of going without them ourselves, as if our abstinence and not their happiness was the important point. I do not think this is the Christian virtue of Love. The New Testament has lots to say about self-denial, but not about self-denial as an end in itself. We are told to deny ourselves and to take up our crosses in order that we may follow Christ; and nearly every description of what we shall ultimately find if we do so contains an appeal to desire.