God has built the desire in humans to understand and classify nature. This was one of original man’s first tasks in the Garden of Eden according to Genesis:

Now the Lord God had formed out of the ground all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky. He brought them to the man to see what he would name them; and whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name. So the man gave names to all the livestock, the birds in the sky and all the wild animals. (Genesis 2:19-20)

Yet, since the rebuilding of the earth after the Flood, this task of the classification of nature was not systematically taken up until Aristotle. Though Aristotle’s work in zoology was not without errors; in God’s Story of Grace, the great philosopher provided the grandest biological system of the time which forwarded humanity’s understanding of the great order and variety of the created world. His observations were so wide ranging to include the anatomy of marine invertebrates; the minute details the embryological development of a chick, and even the internal anatomy of snails. He went into such variety to describe the chambered stomachs of cows to the social organization of bees. Some of his observations were not confirmed until many centuries later.

As a philosopher, Aristotle is largely known for his instruction in logic, ethics and virtue. Yet, his work on the biological order of life left an enduring mark on the advancement of scientific understanding. Before Aristotle, philosophers like Heraclitus, Empedocles and Democritus focused on offering quasi-scientific explanations of the physical universe based on philosophical ideas. Aristotle largely discarded that and sought to base his views of the world on painstaking observation. What drove him to do this extremely detailed and complex work was his belief that all of nature has a logical purpose and order which could be studied and understood. This belief in a logical order and purpose of the world was grounded in his theology (belief about God). Theology, for Aristotle, was an invitation to biology. Studying living things was a way to understand the divine nature. In even in the most most humble of animals, Aristotle reasoned, there is order and beauty that reflected a divine reality.

In this article, the second on Aristotle, we will uncover the order of Aristotle’s discoveries and how his theology drove those discoveries. We will then conclude how he advanced God’s Story of Grace in the area of science.

Aristotle’s Science

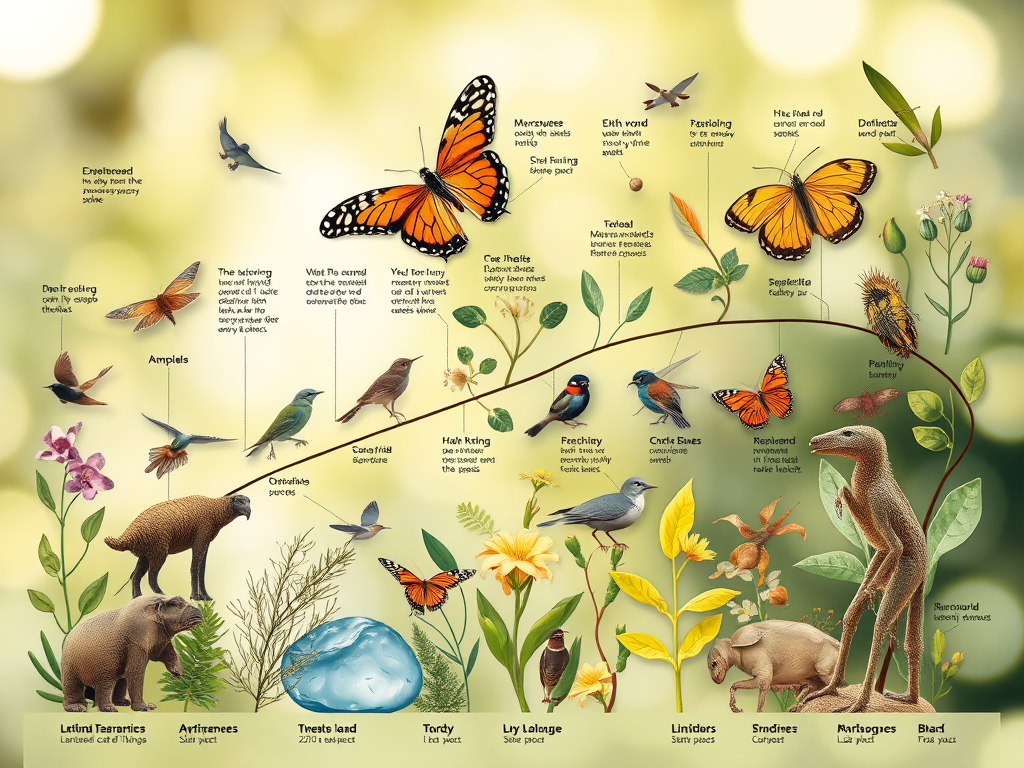

Aristotle was the first to conceive of a great chain of being among all living things. He took his observations of living things and ranked them based on complexity. The greater the complexity the higher its place of the great scale of being. For example, he distinguished animals from plants, because animals have a consciousness and can move in their surroundings. Among animals he created a hierarchy based on their complexity. He separated vertebrates from invertebrates. Of the vertebrates he included five genera (a classification of common characteristics bearing similarities to the biblical “kind”). These include:

- mammals

- birds

- reptiles and amphibians,

- fish

- whales (which Aristotle did not realize were mammals).

The invertebrates were classified as:

- cephalopods (such as squid and octopus)

- crustaceans

- insects

- shelled animals

In total, he classified about 500 animals, vertebrae and invertebrate, into the genera listed above. As already mentioned he classified plants, as well.

What Motivated Aristotle?

Aristotle saw organisms as having an inherent structure and purpose which leads to the overall function of the organism. This structure and purpose he called “soul.” By this he did not mean an immaterial identity separate from the physical/biological structure. The soul for Aristotle is the function of the physical organism inseparable from the body. By this definition even plants have souls. Because of this he believed all living things could be classified because all living things have a purposeful function (soul). So, where did this inherent purpose come from? The answer for this monumental thinker is God.

His understanding of God was not the same as the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob or the Jews. There are some similarities, but the differences are significant.

Similarities:

- God is the highest being over all other beings.

- God is pure purpose, existing without matter.

- God is the unmoved mover, the first cause of motion in the universe.

- God is the source of order and purpose in the world.

- God is eternal.

Differences:

- God is not personal.

- God does not have a plan for us.

- God is not affected by us.

What does all of this mean?

The advancement of science is driven by faith.

Aristotle did not come to believe that the world has purpose and order because of science; rather, he believed that the world had purposeful order, so he pursued a scientific understanding. His theology drove his science. Without the prior belief, he would have had no basis or motivation to do the meticulous research he did. It was clear to him that all of nature did not function by random chance, and that there is an order to be discovered. Everything which is purposeful necessarily is based on purposeful (intelligent) action. For example, imagine two men surprisingly meeting in a clothing store who happen to know each other, and in the process of meeting they strike up a conversation leading toward a business deal. The chance occurrence was based upon their prior and purposeful choices to go to the clothing store to buy a shirt (or whatever item). Chance occurrences, as we observe them, all occur from goal oriented or purposeful action not the other way around. Spontaneity and chance come after thoughtful purpose.

Aristotle sums it up well in his work, Physics:

Spontaneity and chance, therefore, are posterior (follow) to intelligence and nature. Hence, however true it may be that the heavens are due to spontaneity, it will still be true that intelligence and nature will be prior causes of this All and of many things in it besides.

Purposeful design and unguided evolution have an ancient contrast.

It is important to realize that Aristotle’s view of the purposeful order of nature was not at all taken for granted in the intellectual climate of the Greek world he inhabited. Aristotle references, in his work, Empedocles (495–435 BC), who proposed that nature consists of a primordial state where different organs and parts of animals were accidentally and randomly combined in different configurations. Empedocles thought that these early creatures were monstrous and unfit for life, and that most died out. He believed that the remaining creatures who survived were the result of natural selection, which removed the freakish creatures and left the ones that were best adapted to the environment. This is an early version of survival of the fittest. Those configurations which were most fitting survived, while others perished. Empedocles wrote as follows:

From it [the earth] blossomed many faces without necks,

Naked arms wandered about, bereft of shoulders,

And eyes roamed about alone, deprived of brows.

Many grew double of face and double of chest,

Races of man-prowed cattle, while others sprang up inversely,

Creatures of cattle-headed men, mixed here from men,

There creatures of women fitted with shadowy genitals.

Philosopher and theologian, Joe Carini, comments on how modern science confirms the viewpoint of Aristotle over Empedocles.

…our world is not at all like the world Empedocles imagined. Instead, we encounter a world replete with bodies that have a highly complex but ordered and functional arrangement of their parts. What is more, each of these bodies is self-reproducing, by a system that itself is highly complex but ordered and functional. Even more, these bodies exhibit engineering down to the molecular level, with parts so exquisitely ordered to a purpose that they easily surpass the best of engineering done by humans.

The advance of science confirmed revelation in scripture.

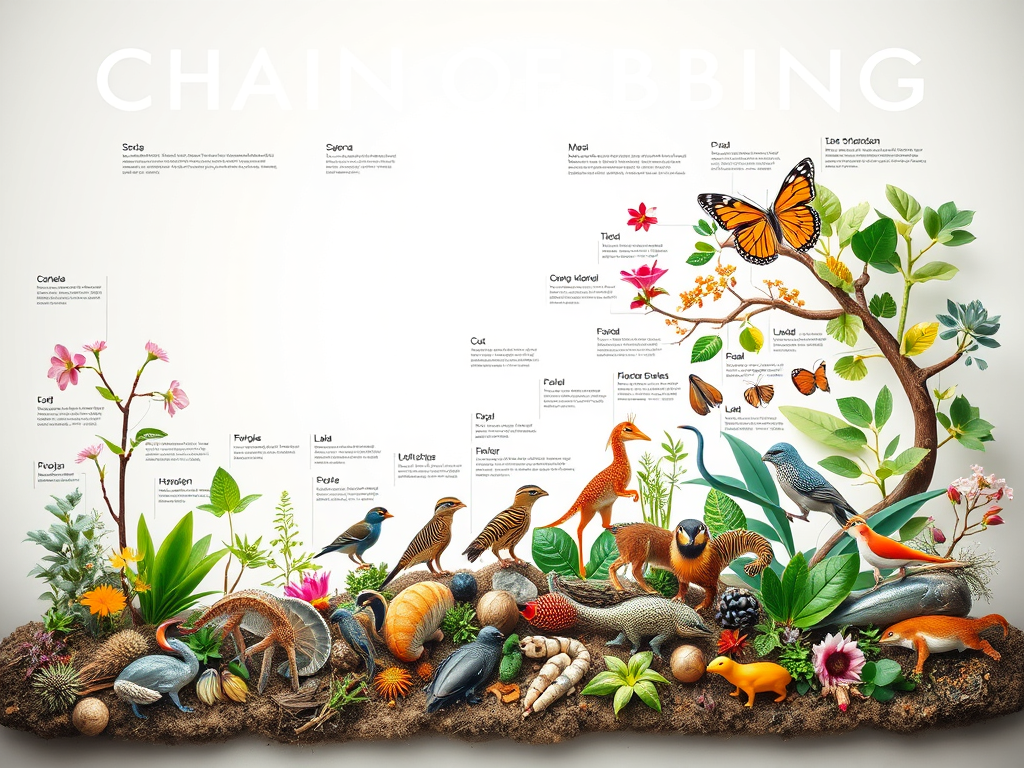

In Genesis 1 it describes a biological categorization similar to what Aristotle discovered by using the word kind. We see the designation kind used three times relation to vegetation and plant life:

11 Then God said, “Let the land produce vegetation: seed-bearing plants and trees on the land that bear fruit with seed in it, according to their various kinds.” And it was so. 12 The land produced vegetation: plants bearing seed according to their kinds and trees bearing fruit with seed in it according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good. (Genesis 1:11-12)

Then we see the designation of kind used six times in reference to animal life:

20And God said, “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the vault of the sky.” 21 So God created the great creatures of the sea and every living thing with which the water teems and that moves about in it, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. 22 God blessed them and said, “Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the water in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth.” 23 And there was evening, and there was morning—the fifth day. 24And God said, “Let the land produce living creatures according to their kinds: the livestock, the creatures that move along the ground, and the wild animals, each according to its kind.” And it was so. 25God made the wild animals according to their kinds, the livestock according to their kinds, and all the creatures that move along the ground according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good. (Genesis 1:20-25)

The term “kind” refers to broad categories of genetically related organisms which can breed and reproduce. This “kind” in Genesis has a nonchanging “fixity” within the design of the biological order. Kinds do not change. This means, for example, that the canine “kind” which includes the dog or dingo or wolf or jackal can reproduce together because they are members of the same canine kind. The canine kind can adapt into different species within their kind through breeding and environmental influences (e.g., chihuahua), but they do not change into another kind like a feline (cat).

Paul writes:

For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made…

Romans 1:20

Aristotle wisely helped us to understand this.